It’s difficult for those who didn’t live through it to explain the tensions and fears of the Cold War. I joined the RAF in the early 1970s, at its height. I didn’t sign up through some sense of patriotism or to save the world. I certainly wasn’t (still ain’t) brave. I just wanted to fly jets, but when that didn’t happen (I wasn’t good enough, I was a danger to all those around me, see previous blogs!) I transferred to the Provost Branch instead. Little thought went into this decision; I wanted to stay in the RAF as it was a good life for a young officer, the beer was cheap, we’d get a married quarter, we’d see the world, and the social life was a joy. I was a deep thinker even in those days…!

Provost officers come from a long heritage, they assist the Provost Marshals, those persons originally in charge of discipline within each Service. In 1629, the Articles of War of Charles 1 of England defined the position of Provost Marshal and his responsibility: “The Provost must have a horse allowed him and some soldiers to attend him and all the rest commanded to obey and assist or else the Service will suffer, for he is but one man and must correct many and therefore he cannot be beloved. And he must be riding from one garrison to another to see the soldiers do not outrage nor scathe the country”. In the RAF, today and in my time, this role had uniquely evolved to encompass the whole range of policing, criminal investigations, physical security, vetting, counter espionage and counter-intelligence duties. This multi-disciplined function is a source of huge pride to the Provost Branch and the RAF Police whom they command – in other Services these various roles are distributed but we did and still do the whole lot.

I did my initial training at RAF Newton in 1976 and my first posting was to RAF Lyneham as Station Security Officer. Thus, by default, I found myself in the very front line of the invisible, insidious and dangerous conflict that was the Cold War.

Initial Provost Officers Training Course – RAF Newton 1976

I wasn’t sitting in a fighter jet or driving a nuclear bomber. I wasn’t a deep cover spy or secret agent. No one was shooting at me, the Russians didn’t even know or care that I existed, my part was miniscule and ultimately irrelevant. But they also serve who only get dragged in by mistake and don’t even realise the seriousness of the situation that surrounds them.

“I found myself in the very front line of the invisible, insidious and dangerous conflict that was the Cold War”

My masters realised very early in my military security career that I couldn’t march, or command men effectively, or simply fire a gun straight. (Indeed, firearms have always frightened me, in flying training I was even terrified of ejector seats – not a good sign in a trainee Top Gun. On one memorable tour of duty later in my career I was required to be live-armed each day with the officer’s recognised personal weapon, the 9mm Self Loading Pistol. Each morning my sergeant would issue me with the damned thing and watch as I loaded and cocked it and placed it in its holster under my jacket. Then as soon as his back was turned I’d unload it, clear the chamber, empty the magazine and put the bullets in my pocket confident in the knowledge that I was one thousand times more likely accidentally to shoot off my own bollocks than I was to be attacked by a terrorist. Of course, neither happened so in my mind I was proved right. But at the end of my tour, at my farewell drinks party, my troops presented me with an empty magazine beautifully mounted on a polished wooden plinth; of course, they’d all known all along.) But at least I was always turned out smartly, was polite, and could write well. Others tell me with hindsight that I was more Sergeant Wilson than General Patten, an Inspector Morse rather than the Sweeney. I could muster a parade if I had to, but it was more of a conversation with the troops than barking out orders. I could hear a disciplinary charge if I needed to, but I always felt slightly embarrassed, telling the miscreants I was disappointed with them and asking after their welfare and apologising but would they mind doing a few extra duties in the Guardroom.

With hindsight I realise many were laughing at this awkward, gangly swot of a young officer but fortunately at the time I lacked the social awareness to notice. I suppose it was thus inevitable that I would be steered towards more scholarly, bookish roles and this became a pattern over my years in the RAF. Good men at the top recognised my several strengths and many more weaknesses and took me under their wings – I remain close to them to this day. If there was something new that needed figuring out I’d be set running (that’s how I got into computer security as early as 1981). If new ways needed devising or new policy setting then that became my forte. If something was tedious, or needed explaining to non-specialists, or required just a bit more detail, or thought, or demanded some patience and perseverance then I was brought in, all the better still if I didn’t have to look after any troops.

Thus, by the summer of 1978 I was becoming less of a rooky military police officer and more specialist in my roles. Though very young and still work-in-progress I was posted to RAF Germany’s Joint Headquarters (JHQ) at RAF Rheindahlen for three years as head of special investigations – equivalent to the CID in the civil police. But my tour almost ended as soon as it had started.

“I was posted to RAF Germany’s Joint Headquarters (JHQ) at RAF Rheindahlen”

Back then services personnel were able to buy new cars tax-free, it was standard practice to visit the JHQ NAAFI car showroom even before you’d unpacked your boxes to order your new Volvo estate, Mercedes saloon or fully loaded Range Rover. The huge Peugeot 504 estate with seven seats was especially popular with the family man. Modestly, I’d the small BMW in my sights, perhaps the new 318 range, ideally the two-door saloon in flame orange – don’t judge me, that colour was then all the rage.

On my second day in Germany I spotted such a model in that colour, brand new, parked in the NAAFI car park. My heart was lost. I peered into it, got on my hands and knees to inspect its underside, stroked the smooth bodywork, tried to door handle to see if it was locked (it was), and gazed at it for many minutes lost in my dreams. That same evening the entire area was cordoned off when it was discovered that the car contained 500 lbs of high explosive, it had been planted there several days before by the IRA but had failed to explode. Earlier that week, eight military barracks from Monchengladbach to Herford had already been bombed in a coordinated attack, this one was planned to be the “spectacular”, but its detonator failed to function. I’ve never been a fan of the BMW since. (Ten years later that IRA struck again at Rheindahlen, this time successfully detonating a car bomb that killed several and injured many).

The NAAFI store at JHQ Rheinhadlen.

My patch was the whole of Germany, and for the following three years I enjoyed one of the most fascinating and rewarding jobs I’ve ever had. In preparation I’d been sent on the 12-weeks’ Home Office Detective Training Course but of course I had not one iota of practical experience in investigating crimes of any sort. Fortunately I had under my command a very small team of hardened police investigators led by a gnarled and cynical Warrant Officer who made it clear from the first day that he was really in charge, but that if I behaved myself and did what I was told then he and “his” sergeants would do their utmost to look after me and teach me everything they knew. I took the hint, relaxed into their guidance and learned quickly. They were good and loyal men (no women in those days, I’m afraid) and I hope I was a worthy student.

Officers were required to wear hats; note the flared trousers.

My work led to strange things. I was also the Coroner’s Officer for the Region and attended many dozens of postmortems in the morgue of the RAF hospital at Wegberg. Indeed, the pathologist Ian Hill became my closest professional friend; he went on to become the expert advisor for the original series of the long-running tv programme Silent Witness.

I travelled the length and breadth of Germany. I and the team investigated attempted murders, manslaughters, arson, criminal damage, sudden deaths, assaults of all kinds and severities, fraud and the whole range of other routine crimes that occur in any community. To my shame we even investigated those officers and airmen whose offence was to be gay – back then, although homosexuality had ceased to be a civil crime it was still a military offence and was studiously pursued by the Services as “a threat to good order and discipline”.

Many of my investigations required tact, sensitivity and diplomacy and I proved surprisingly effective in my job. I grew up quickly. But underlying everything, as a compelling unconscious presence, was the constant threat of nuclear war. Germany really was on the front line between East and West. The armed forces of the UK, US and France (in the west) and Russia (in the east) were there still as occupying forces. World War 2 was still a very recent and raw memory to the German population with whom we had to live and work, the whole environment was a political minefield. Tensions between the East and West were as high as they’d ever been. Both sides had huge armies lined up at the border and massive nuclear arsenals trained in each other’s directions and on hair triggers. It had to be assumed that spies were everywhere and that a single spark could set off the whole tinderbox.

It was in this highly dangerous and sensitive context that in their wisdom my bosses sent this naïve and still highly inexperienced young officer off to Berlin to investigate reports that a German civilian employed at RAF Gatow had been passing sensitive military secrets to the Russians.

“It had to be assumed that spies were everywhere and that a single spark could set off the whole tinderbox”

It was my James Bond moment, the one I’d been waiting for. But instead of Miss Moneypenny and an Aston Martin, I had Sergeant Bob Steele and a green Mk4 Cortina. Our fleet of police vehicles were supposed to be undercover, but the tyre pressures painted over the wheel arches, the WD Fire Extinguisher mounted on the transmission tunnel and the massive whip aerial sticking up from the rear wing did rather give the game away. Nevertheless, excitement was high in this crack team of super sleuths; with Bob driving and me dozing we sped across the plains of Germany towards our distant destination of Berlin.

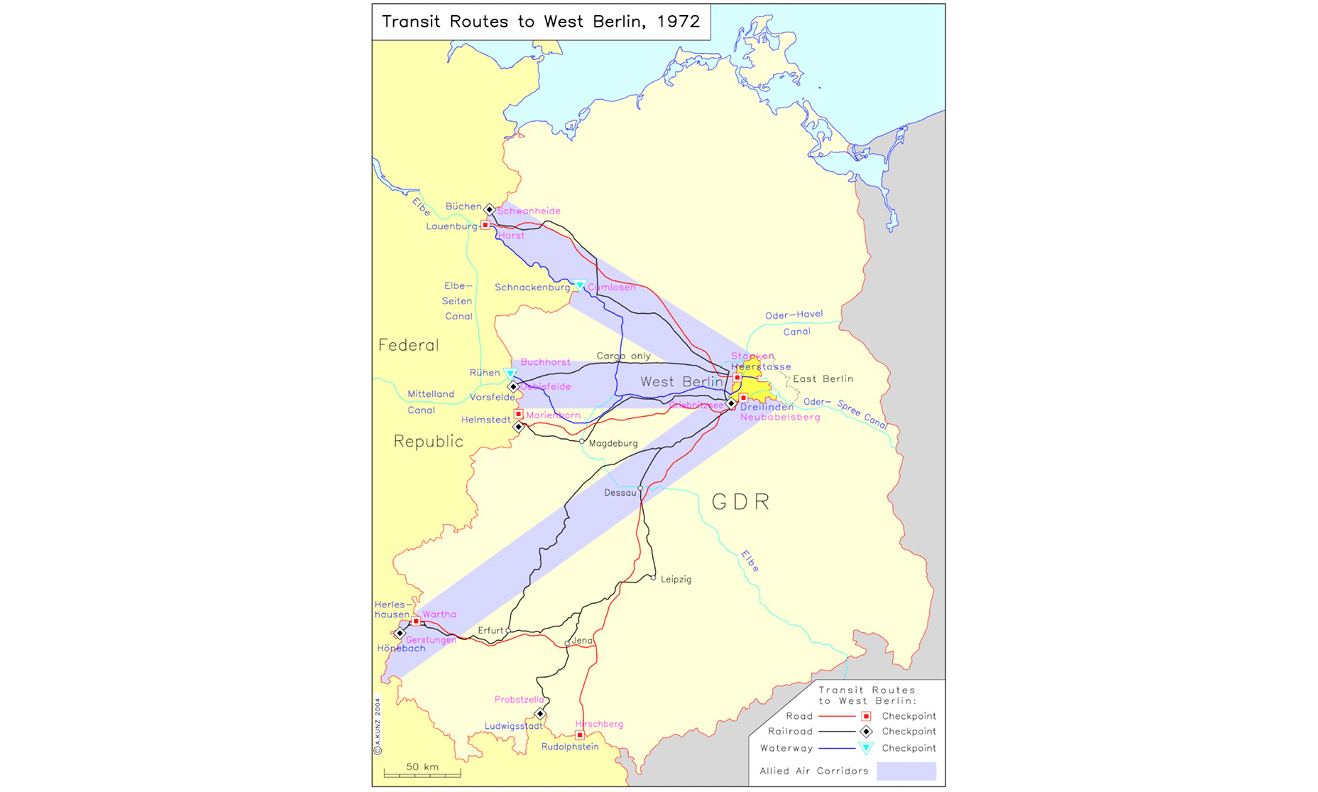

At the end of the war, Berlin had become an isolated enclave deep within East Germany and surrounded by Russian-controlled territory. The city itself was segregated into the French-, US- and UK-controlled zones (West Berlin) that were eventually to be cut off entirely with the building of the Berlin Wall, and the Russian-controlled zone (East Berlin). The post-war agreements on the governance of Berlin specified that the Western Allies (i.e. me and Bob) were to have access to the city only via defined air, road, rail and river links. We thus headed directly to the East/West German border crossing at Helmstedt (Checkpoint Alpha) where we would be granted access to the highly restricted and controlled road corridor leading to West Berlin at Checkpoint Bravo. (The more famous Checkpoint Charlie of the John le Carre stories was then at the other side of West Berlin leading into East Berlin.)

Checkpoint Alpha was the largest and most important of all the border crossings, providing the shortest land route between West Germany and West Berlin. Road crossings were straightforward but slow, subject as they were to endless border formalities and inspections, and reams of forms and paperwork. Then there was a strict speed limit of 70 kph (43 mph) along the entire 110 miles of the designated route across East Germany. The fearsome East German and Soviet border guards timed you as you set off and again when you got there; if you arrived at the other end too soon you were done for speeding by the Royal Military Police; too late and it was assumed by the Russians that you’d deliberately strayed off course to do some illegal spying and you’d be arrested and never seen again. Either way you were screwed, especially if to boot you were military security personnel in civilian clothes travelling in a covert vehicle, so this was not a trivial exercise and it required some significant concentration if Bob and I were to get it right. I suspect, dear reader, that you may already have guessed where this story is leading.

But it gets worse. As tensions had risen in the early 70s the East Germans had only just extensively increased the scale of their security operations at Checkpoint Alpha. They’d built their own new massive facility on a hill about a mile to the east of the original, as big as a town, manned at all times by hundreds of passport control and customs officers and border police. There was even a tunnel system through which additional armed military support units held in constant readiness could be deployed in case of trouble. They were taking this border thing very seriously, and their awe-inspiring set-up now contrasted significantly with the original, modest operation still being run by a small number of French, British and American military police personnel working out of the original huts. Whilst the West was trying to play the tensions down, the East were determined to display their strength.

The two halves of the checkpoint (West and East) were connected by a mile of no man’s land, the road heavily and suspiciously guarded by the East. As two great armies lined up against each other along thousands of miles of international borders across great continents, Checkpoint Alpha was where they came the closest, where their noses touched, where they stared into each other’s bloodshot eyes and smelled each other’s fetid breath. Tense doesn’t even come close as a description of the atmosphere.

The Western end of Checkpoint Alpha, as it was on that fateful day.

I was driving as we approached the Western end of Checkpoint Alpha. Sergeant Steele was in the passenger seat clutching the cardboard file of paperwork closely to his chest, ready to jump out of the car and check us in with our side. We were both on high alert. A building sat in the middle of the road, carefully I crawled past a row of vehicles parked beside it, I could see no one, it seemed all very quiet. A red-capped RMP corporal gave us a friendly wave, I waved back and kept going. A large gravelled parking area to the left looked as if it was for a café, I waited for inspiration from my navigator as to what to do next. “Keep going, boss,” he said, his head buried in the paperwork. I kept going. “Are you sure, Bob?” I asked. He looked up and peered through the windscreen. “Yes. It has to be over there, keep going,” he said, pointing ahead. I kept going. “Where now?” I asked, a little more sharply this time as high fences and barbed wire crowded in on us. I noticed a watchtower to our left; it sported a large machine gun that was now tracking our progress. The road narrowed further, the fences either side got higher, armed guards magically appeared out of trenches and pointed their weapons at us; worryingly, these soldiers were dressed in uniforms I didn’t immediately recognise. Bob had fallen strangely quiet and subdued. I think we’d both realised at the same moment that something had gone horribly wrong. I kept going, it seemed the only thing to do.

For what seemed a lifetime we eased our way along, and after about a mile uphill we reached – yes, you know this already don’t you – the Eastern Checkpoint Alpha. We’d entirely missed our own checkpoint and were now a mile deep into enemy territory. East German border guards were waiting for us, three of them lined up across the road with rifles held at the ready – though encouragingly not pointed straight at us.

The bonnet of the Ford stopped just short of them as I pulled to a halt and put on the handbrake. The guards seemed strangely puzzled more than aggressive. I turned off the car engine, it felt the right thing to do, and smiled nervously at them. One of them smiled back. Slowly I opened the door and got out. Out the corner of my eye I could see Bob had done the same, he had a working knowledge German and was saying something I didn’t understand but it sounded friendly. He was smiling broadly, and then one of the guards said something back and the rest of them (and Bob) laughed. The guards’ rifles dropped further, then were slung over shoulders, the dynamics seemed pleasant enough. A few others joined us from surrounding buildings. Everyone seemed relaxed. Bob was still chatting away, then he moved towards them with his hand outstretched, then he was shaking their hands in turn.

“Three of them lined up across the road with rifles held at the ready”

Suddenly I needed to piss. This bodily urge overtook everything, it became my entire focus. If I didn’t do something very quickly then I would surely embarrass myself and everyone else, and it wouldn’t help that I was wearing a pale grey suit. Through the open door of the East German guardroom I could see a toilet. I pointed at it, grimacing and holding my crotch in the universal language of anyone desperate for the loo. One of the guards inside waved at me encouragingly, I needed no second invitation and I went through and relieved myself. It was pure bliss, the best I’ve ever had.

The guardroom itself was like every other I’d been in. It looked the same, it smelled the same, the troops inside it could have been from any army and they all smiled and nodded at me as I went back to the car. By now there was a small crowd around the vehicle, laughing and chattering as Bob distributed packs of Silk Cut cigarettes to the soldiers. (We all smoked like chimneys back then, Bob and I had grabbed a couple of packs of 200 from the NAAFI before we left to last us for a week or so, the cartons had been chucked onto the back seat.) I held back – I was the young officer, Bob was a sergeant mixing with his contemporaries, he had established the rapport, I would have broken the spell. There was another young man who similarly stood back, we looked at each other awkwardly, I realised he was their officer and he seemed equally unsure of what to do.

With a flourish and small bow from the waist, one of the East Germans presented Bob with a small item, I couldn’t see what but it was obviously something of value, Bob looked across and indicated with his eyes that it was time we should leave. I got back in the driver’s seat, he joined me in the car, I carefully turned around and drove slowly back the way we’d come. Bob was waving out of his open window. In my rear-view mirror I glimpsed a now-significant crowd of soldiers smiling and waving back. The guns either side of the road continued to track us but in some way didn’t seem as threatening.

Bob was examining the small gift he’d been given. “What’s that”, I asked. “It’s a buckle off one of their belts”, he said. I learned later that such a gesture of exchanging kit, especially uniform buckles and buttons, was very special, a true sign of friendship between comrades. Other than these words, we travelled in silence back to our own side.

“In my rear-view mirror I glimpsed a now-significant crowd of soldiers smiling and waving back”

I have thought many times over the past forty years of the significance of those few strange minutes. All around us the world was at war, entire populations were living in a state of terror, in fear of nuclear Armageddon. International relations were extraordinarily tense with Presidents and Prime Ministers at loggerheads, each side puffing up and posturing, both sides irreconcilable. But at an individual level, those facing each other on the actual front line, those who would die for the causes of others, those standing in the cold and whiling away endless days of boredom and nothingness away from their families, they were just blokes. This was my Christmas Day football match moment that put everything back into perspective, then and since. Its impact on me has stayed for ever.

Of course, by the time we got back to our side all hell had broken loose. A welcoming party of the Royal Military Police was waiting for us in the “café car park” (which turned out to be the main marshalling area for cross-border traffic). A very red-faced RMP Warrant Officer ripped open my car door and hurled a stream of rich abuse as I climbed out. Bob and I were marshalled into the checkpoint office and asked to explain ourselves to a senior Army officer whose opinion of the RAF was already clearly not high, and we’d done little to help improve it. “We just didn’t see the checkpoint, sir”, I said. He leaned forward. “We get 250,000 people through here each year”, he said ominously quietly. “I’ve been here for three years and you’re the first fuckers who’ve ever missed us.” I had no immediate riposte. Silence seemed the best option.

Things moved quickly then. We were escorted by the RMP through both halves of Checkpoint Alpha without stopping, thus avoiding further contact with our newly-formed “friends”, and then all the way non-stop to Berlin. We followed their Range Rover at high speed to Checkpoint Bravo, obviously ignoring the speed restrictions along the way. We were met by an RAF Police Range Rover and followed that vehicle straight to RAF Gatow. We parked at Station Headquarters and I was marched alone into the senior Provost Officer’s office, a delightful old timer whom I’d met a couple of times before at Rheindahlen. “What have you done this time, Smith?” he asked, though not crossly. He seemed quite amused.

“A welcoming party of the Royal Military Police was waiting for us”

Apparently the incident had been escalated to Ministerial level, Governments had spoken, and even as we were driving to Berlin the British Ambassador in Bonn had been on the telephone to Gatow. I feared the worst. I gave a verbal account of affairs but without expanding overly on the details of what had happened at the East German checkpoint, I merely said we’d turned around and driven back. Obviously I was most apologetic, and as my explanation stuttered to a close I held my breath for what was to come next. Court martial? Dismissal in disgrace from Her Majesty’s Service. Public humiliation?

“I reckon you could do with a stiff drink, Smith,” he said. “You’ve had quite an afternoon and caused a bit of a stir. But no harm done, eh?” And with that we went to the Officers’ Mess bar, I did drink quite a lot, and we were joined by an increasing number of other officers who all wanted to hear my story.

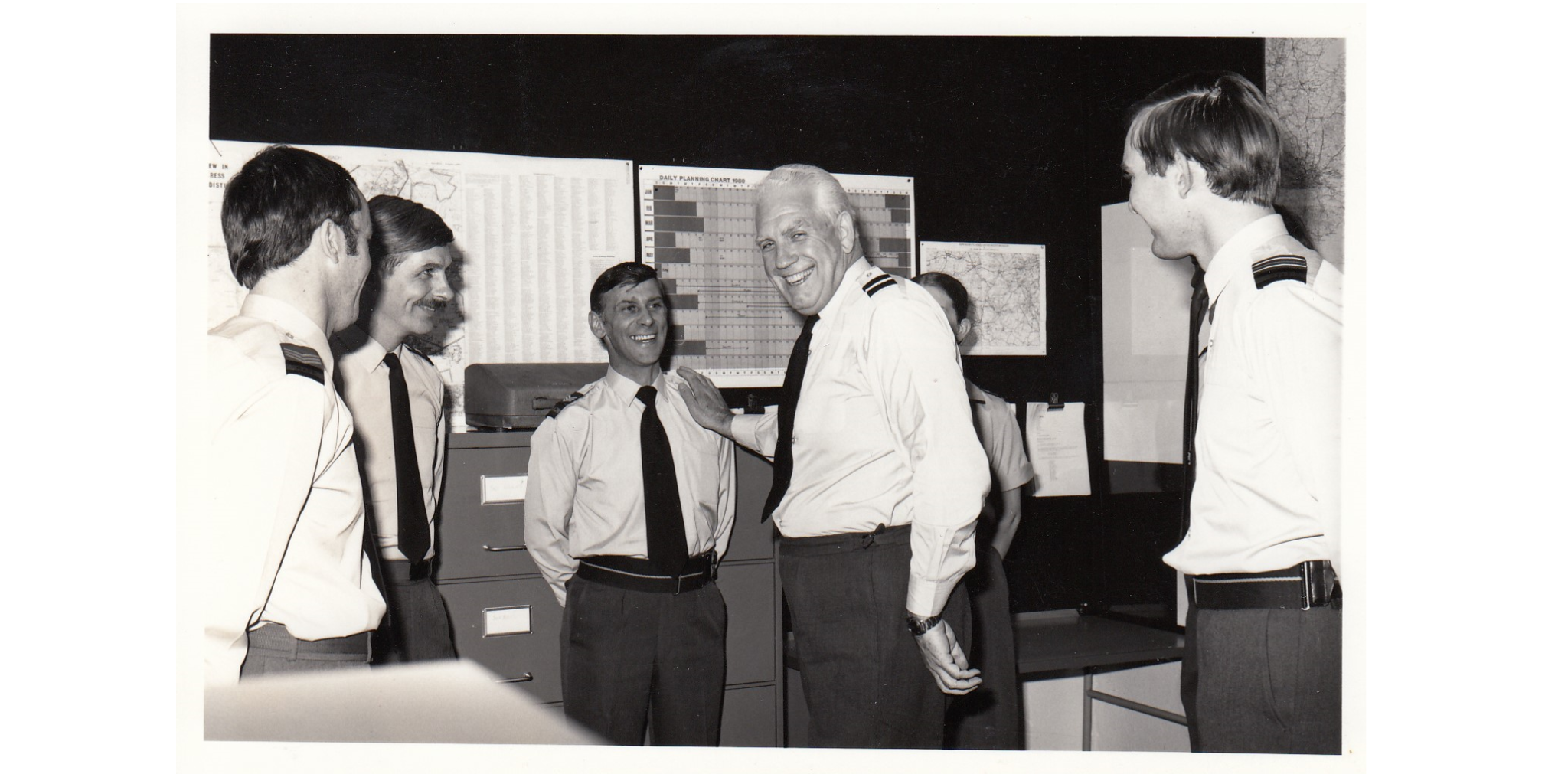

But after that evening nothing more was ever said. Bob and I caught our “spy”, a sad local minion selling for peanuts small snippets of gossip he’d overheard whilst working on the camp. We drove back to Rheindahlen without incident this time. I got my leg pulled a couple of times back in the office. To this day I have no explanation as to why no great international incident ensued, or why I wasn’t Court Martialled for my stupidity. I’m guessing that since no harm was done then the system preferred to play the whole thing down, let common sense prevail, avoid further embarrassment, and let sleeping Russian bears lie. The following year we were visited in Germany by the Provost Marshal and he seemed friendly enough.

To be fair, I was never sent to Berlin again.

All good friends again and no harm done… My team meeting the Provost Marshal in 1980.

Bob Steele is standing second from the left. I’m the streak on the right.

So, my claim to fame, and one that is unlikely ever to be challenged, is that I am the only serving RAF Officer to have had a piss in an East German guardroom whilst on active service at the height of the Cold War. Unless you know of another…

To comment on this blog, visit Martin’s LinkedIn article here…

Read more of Martin's Log

Thank you for reading my blogs. I’m getting quite old now, and hopefully I’m a little wiser than I once was. I have enjoyed a fascinating career full of fascinating people, and made many great friendships. I’ve made huge errors in my lifetime, and enjoyed great success too – it’s been the ultimate game of snakes and ladders - up and down, round and round. It is my privilege to share some of my stories with you, and describe some of the lessons I’ve learned in the hope that it may both save you from falling into the same holes, and help you in your careers and lives. Good luck and good fortune.

More blogs